Since the early 1800s, Wheeling has played a crucial role in bringing people and products to and from West Virginia. The convergence of the Ohio River, National Road and the B&O Railroad made Wheeling a natural setting for growth and development.

In the late 19th century, Wheeling was completely self-sufficient, manufacturing all goods and services and growing all foods within its borders. This era marked the city’s most intensive industrial period; the wealth generated by this industry and commerce produced much of the city’s Victorian architectural legacy.

Products like the ones below weren’t just made in Wheeling – they also helped make Wheeling what it is today.

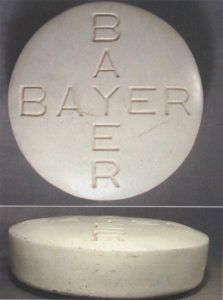

Bayer Aspirin

While much of Wheeling was busy inventing and manufacturing products, Wheeling-based Sterling Products was in the process of introducing one of the most revolutionary pain relieving drugs to the United States – the aspirin. The genius of the company was not in its innovative research but in its brilliant and prescient marketing of up-and-coming pharmaceutical products, particularly patent products that thrived in rural areas. Started in 1901 by a drugstore clerk, William Erhard Weiss, and his high school friend, Albert H. Diebold, Sterling began as the Neuralgyline Company. The company aggressively marketed its patented pain reliever, Neuralgine. With $10,000 in sales in the first year alone, the two men invested in advertising campaigns in the Pittsburg market for their product. They had amassed so much money by 1907 that the two purchased the Sterling Remedy Company and changed the name to Sterling Products later changed to Sterling Drug, Inc. in 1942).

When the U.S. government seized the German-owned Friedrich Bayer Company’s American holdings after World War I, the Alien Property Custodian auctioned the American Bayer Company. Sterling Products of Wheeling put forth an astounding $5.3 million to acquire the company’s U.S. holdings. In the process, it became the owner to the patent of one particular scientific breakthrough – aspirin. It consisted of synthesized salicylates, which naturally occur in the bark of willows and other plants. In 1921, after a U.S. judge allowed the use of “aspirin” as a generic term, Sterling attached the name “Bayer” onto its products. Ironically, after months of domination of the worldwide market for aspirin, Sterling eventually ran into stiff competition in the 1920s from its German counterpart, I.G. Farben, Bayer’s new parent company. In what became a major transformation for Sterling, the two parties agreed to exchange holdings. Sterling would give Farben half of its stock in its laboratory subsidiary, Winthrop Industries, in exchange for Farben’s manufacturing and patent data for future discoveries. The profit potential for Sterling was huge, which management placed at upwards of $100 million.

The effect of this allowed Germany to “colonize” markets. Sterling came close to violating the U.S. government’s sanctions of German products during World War II when it exported some of its products to other countries’ markets, which were derivatives of its earlier patent sharing with Farben. However, through savvy public relations, Sterling executives managed to avoid any antitrust litigation by the government.

While Wheeling was an ideal market for patent-based medicines that benefited greatly from marketing, by mid0century the company would eventually leave Wheeling for New York City in order to expand its research efforts that a small market could not afford. By the 1970s, sales of Bayer Aspirin reached over $50 million a year. Sterling would go on to purchase over 100 companies and maintain well over 50 plants throughout the world.

This content provided by INWheeling Magazine.